The law governing land ownership and dealings in Malaysia

In Peninsular Malaysia, the National Land Code, 1965 (“NLC”) provides the legal framework for a uniform system of land tenure and dealings in accordance with a system of registration known as the Torrens System.

Before Malaysia’s independence and prior to the introduction of the NLC and the Torrens System, laws relating to ownership of land in the early Malay states were largely a blend of Islamic law and the prevailing local customs with each state practicing its own distinct system of land ownership.

At the time, the Straits Settlements, Federated Malay States and Unfederated Malay States practiced a medley of land tenure systems, rules and administrative procedures pertaining to land. Some of the early systems of land tenure resulted in problems such as difficulty proving the chain of ownership of land, undetected dealings and concealed interests in land. As a result, the land system in the then Malaya could be viewed as fragmented, confusing and simply problematic for the layman.

Post-independence, Parliament passed the NLC as a means of resolving the problems caused by the confusion of systems present in Malaysia. The NLC came in force on 1st January 1966 and was intended as a uniform system of land tenure and dealings in the Peninsular Malaysia which was in accordance with the Torrens System.

The Torrens System

The unified system practiced under the NLC is known as the Torrens System which was based on the Merchant Shipping Act, 1854 or the system of registration of titles named after Sir Robert Torrens, who first introduced it in South Australia.

The Torrens System recorded all ownership of land and put it on a register maintained by the State. This register was then regarded as the authoritative list of ownership and dealings pertaining to any land in question. In other words, the register was everything when dealing with land.

Three main principles underpin the Torrens System, namely:

- The Mirror Principle – the register mirrors the complete and current particulars of all dealings and interest in a particular land.

- The Curtain Principle – since the register is the authoritative and absolute record of the particulars of all dealings and interests in land, there is no longer a need for any interested party to go behind the ‘curtain’ of the register to investigate any further.

- The Insurance Principle – compensation is provided for instance of loss suffered by error made by the Registrar of Titles.

As a result of the above principles, the Torrens System confers indefeasibility of title to the proprietor upon registration.

This meant that, upon registration, the proprietor’s claim of ownership over the land is protected against adverse claims or interests by third parties.

This is probably the most important effect of the implementation of the Torrens System. However, it is worth noting that this indefeasibility is not absolute and can be defeated under certain circumstances (e.g. where there are elements of illegality, fraud, misrepresentation, mistake etc.).

Alienation of Land

Firstly, it is worth noting that for private individuals to own land, the State Authority must first grant the right of ownership to private individuals – this process is known as alienation of land. The State Authority may dispose of state land in for a term of a fixed number of years (leasehold) or in perpetuity (freehold).

As a result, the disposed/alienated land may be subject to a payment of annual rent (quit rent), restriction in interest (sekatan kepentingan), express conditions (syarat-syarat nyata), category of land use, etc.

Document of Title

As discussed above, the right to land in Malaysia is evidenced by the land title, also known as the “document of title”. Section 5 of the NLC defines “document of title” as both the register document of title and issue document of title.

The land title refers to a document intending to evidence the title to land. In Malaysia, this document of title exists in the form of a Register Document of Title (“RDT”) issued and maintained by the land registry or land office and a duplicate or extract of the RDT known as the Issue Document of Title (“IDT”) which is issued to and kept by the registered proprietor. Both the RDT and IDT include a plan of the land certified as correct by the Director of Survey.

A land search may be conducted at the land registry or land office by any interested party. The search is conducted against the RDT maintained by the land office thus revealing all dealings and particulars of relating to the land.

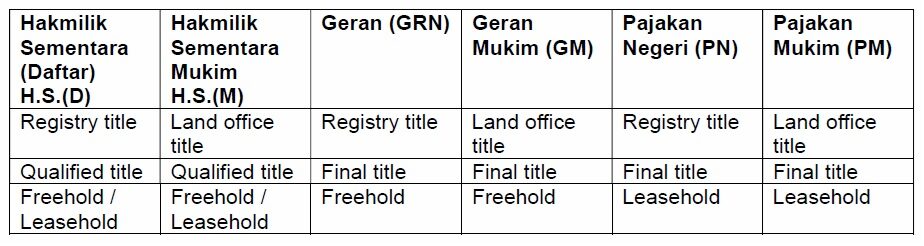

The following are the most common types of land titles in Malaysia. Note that the type of title indicates certain features of the land:

Registry title vs land office title

A land registry known as the Land and Mines Office (Pejabat Tanah dan Galian) is the found in the capital of every state with land offices (Pejabat Daerah dan Tanah) existing in most districts. State land may be alienated under registry title or land office title (being forms of final title) and qualified title where the survey is provisional only.

Section 77(3) of the NLC prescribes for town or village land, country land exceeding four hectares and any part of the foreshore or sea bed to be held under a registry title while country land not exceeding four hectares is to be held under a land office title.

At the land Registry, the appointed Registrar of Titles or Deputy Registrar of Titles appointed under section 12 of the NLC is responsible for registration of titles. Meanwhile, at the land office, the registration of titles is conducted by the Land Administrator.

Freehold vs leasehold title

A freehold title bestows ownership of land on a proprietor for an indefinite period. The proprietor of a freehold land has the perpetual right to use, lease, sell or transfer the land, subject to any restrictions or express terms imposed on the title.

Despite the grant of perpetual ownership, freehold land is subject to state government approval for certain dealings (e.g. transfer and charge), and the land can also be subject to land use restrictions, such as for residential, commercial, agricultural or industrial purposes and subject to zoning laws or planning approvals.

A leasehold title on the other hand bestows ownership of land on a proprietor for a fixed tenure ranging from 30 to 99 years and is stated on the document of title. Upon the expiration of the lease the land ownership reverts to the state or the original landowner unless the lease is renewed.

Aside from the lease tenure, a proprietor of a leasehold land enjoys the same rights as that of a proprietor of a freehold land and has the right to use, lease, sell or transfer the land subject to any restrictions or express terms imposed on the title.

A key feature of leasehold land is that upon expiry of the lease term, the land and any improvements made to it revert back to the state unless a renewal is granted. In practice, the renewal process depends on the policy of the relevant state government, and while some states may allow extensions, others may not.

Qualified vs final title

Section 77(1) of the NLC states that State land may be alienated as either Registry title and Land office title (being forms of final title) and qualified title.

Qualified Title

A qualified title refers to the title issued to land that has not yet been surveyed or registered in full accordance with the National Land Code. Since a qualified title is issued in advance of survey, there is uncertainty regarding the boundary of the land and it cannot be subdivided or included in any amalgamation.

Nevertheless, the registered proprietor of a qualified title shares the same rights as a final title and can transfer, lease or charge the land prior to the issuance of a final title. Land under a qualified title may be converted to a final title once it has been surveyed.

Qualified title may be registered at the land registry (PTG) as Hakmilik Sementara Daftar (written as “H.S.(D)” on the document of title) or registered at the land office (PDT) as Hakmilik Sementara Mukim (written as “H.S.(M)” on the document of title”).

As mentioned above, land registered under land registry title is usually larger than four hectares while land registered under land office title is usually smaller than four hectares.

Final Title

Defined in Section 5 NLC to include the Registry title, Land Office title and subsidiary title (strata title) (that is to say, all forms of title other than qualified title).

Once the survey is completed on the land held under a qualified title, a final title may be issued wherein indefeasibility of title and the right of dealing is guaranteed by section 92 of the NLC (subject to the restrictions in interest and express terms endorsed on the title).

Final titles include:

- Geran (GRN)

- Geran Mukim (GM)

- Pajakan Negeri (PN)

- Pajakan Mukim (PM)

Individual title

Individual title refers to title to land that has been subdivided for an individual piece of property and is no longer part of a larger development, for example, bungalow/semi-detached/terrace houses, shop houses, factories etc.

Master title vs strata title

When a large plot of land is in the process of being constructed into a multi-unit development (e.g. condominium, office building, shopping mall, townhouses etc.) a master title is issued and registered in the name of the developer or proprietor.

Therefore, the entire development project will be held under one master title belonging to the developer or proprietor until the development project is completed and the master title is subdivided into strata titles.

The strata title allows individual ownership of a unit or parcel while sharing ownership of the common property. Strata titles are subject to the regulations set out in the Strata Titles Act 1985, which governs the management of strata developments and ensures the proper maintenance and governance of the common areas.

Particulars endorsed on title

The rights, conditions and restrictions attached to land can be found on the particulars stated on the title. Some of the common title particulars are as follows:

- Type of Title – whether qualified title (H.S.(D) or H.S.(M)) or final title (GRN, GM, PN, PM) – the type of title also indicates where it is held (i.e. whether at the land registry or land office) and whether the land is leasehold or freehold.

-

Ownership No. (No. Hakmilik) – refers to the unique registration number of the land

- Lot Number – Lot means any surveyed piece of land to which a lot number has been assigned by the Director of Survey and Mapping. This is the unique number of the specific parcel of land your property belongs to.

- Classification of land – whether town,

village or country land. Two main classifications of land: (a) land above the

shoreline; and, (b) foreshore and seabed. Land above the shoreline is further

classified as town land, village land or country land. -

Lease tenure – if the property is leasehold, the title will state the tenure of the lease.

- Category of Land Use – whether Agriculture, Building or Industry

- Express conditions – these conditions are imposed by the State Authority and vary based on the land category.

- Restriction in Interest – defined by Section 5 NLC as any limitation imposed by the State Authority on any of the powers conferred on a proprietor under the NLC or previous land law.

-

Previous title number – if the property previously held under a qualified title, the particulars of the previous title will be stated here.

- Amount of Quit Rent payable

-

Record of ownership – the title will state the name, NRIC number abd address of the property owner together with the share of the property held.

-

Encumbrances – including charges (where the property was charged to a bank as security for a loan), caveats, leases, easements, and other restrictions on the land which may be endorsed on the title (e.g. court orders).

Conclusion

Understanding the different types of land titles in Malaysia is critical for anyone involved in property transactions or land ownership.

The primary distinctions are based on the duration of ownership (freehold vs. leasehold), the type of property, and the rights and restrictions associated with the land.

Each type of title carries unique implications for property rights, usage, and transferability, and it is important for landowners, investors, and professionals to be aware of these distinctions when managing or acquiring land in Malaysia.